Independent Collectors

Clayton Press & Gregory Linn

Since 1980, Clayton Press and Gregory Linn – New Jersey collectors – have evolved from being energetic art aficionados to art market specialists.

Since 1980, Clayton Press and Gregory Linn – New Jersey collectors – have evolved from being energetic art aficionados to art market specialists. Art has been and remains central to their personal relationship and professional activities.

They are engaged in art advisory and curatorial activities, as well as criticism and scholarship. Both Clayton Press and Gregory Linn are well known as early identifiers of emerging talents, many of which have developed into artists who are well recognized in the contemporary canon – from Richard Prince to Diana Thater, from Jutta Koether to Borna Sammak. Their collecting approach was transformed by a visit in the 1980s to the Hallen für Neue Kunst, Schaffhausen, Switzerland, where they decided to focus on artist careers rather than individual works.

In collaboration with Art Cologne, IC speaks to the two collectors about their relationship with art and the recent bequest of their estate to The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

IC

You started collecting together in Chicago in 1980. Can you tell us how your interest in contemporary art began and evolved?

CLAYTON PRESS & GREGORY LINN

I had studied cultural anthropology, art history, and Africana Studies as an undergraduate, taking a triple major. This was the academic foundation for my PhD studies in anthropology. Diversity of expression was key. To this day, we think that many of the most compelling, visually interesting collections are syntheses of history, content, material, and media. To see indigenous art on an 18th century hand-painted table in front of an 21st century ink-jet painting is often inspired chaos.

Greg’s interest in art developed almost immediately after we met. Because he had grown up in rural Illinois, it was not until he had moved to Chicago that he had access to museums, galleries, and other art venues. His immediate interest and enthusiasm for contemporary art propelled and accelerated our collecting activity.

IC

As a couple, how do you decide which artists to collect?

CLAYTON PRESS & GREGORY LINN

Aside from a few early purchases, we have always made decisions together, collaboratively. It is unusually easy for us. Neither of us holds sway over the other. We are interested in ideas first, and the way that ideas are manifested as objects second. Sometimes Greg introduces an artist to me and encourages my support. Kay Rosen is one of those artists. I introduced him to Win McCarthy.

It is a perpetual dialogue. We continuously talk about art, read about art, and most importantly look at art, in person and online. It is a nearly daily activity, in part because we engage in the market in a variety of ways. Ultimately, we trust our instincts, whether we are adding to our collection or recommending a purchase to a client.

For us personally, the art – the ideas – has to be fresh. Theme and variation can be interesting, but we want to associate our collection with new ideas; ideas that make us think differently, ideas that challenge us. When you think about genuinely great achievements in art, you think about those artists who challenged the status quo, even if only briefly. They somehow broke through, doing something different. Few artists have long, compelling careers. Greatness resides in innovation and evolution.

Quality is paramount. The work has to be the best that we (or our clients) can afford financially. Sometimes you have to stretch your budget or sacrifice one work for another or several others. You have to be resolute about the process of discernment. Invariably, after visiting an exhibition, Greg and I like the same works, most often using the same rationales or criteria.

Another essential aspect to collecting contemporary art is to keep an open mind. Sometimes the magnetism is nearly there, but more time and experience are needed to have certainty, “to know.” We personally experienced this with the work of Franz West and Christopher Williams. Our epiphanies did not occur in a first, second, or even third encounter. Nonetheless, both artists’ works were so compelling that we kept looking, learning, and finally collecting. When we “awoke” – and we can both remember the exact place and time for each artist – we awoke with absolute clarity.

IC

You started collecting art when you lived in Chicago in the 1980s. Shortly thereafter you got engaged in the New York and Los Angeles markets. How did your collection evolve?

CLAYTON PRESS & GREGORY LINN

As young collectors in Chicago, we saw and bought art locally. We collected what we saw, what was in front of us. We grew into more diverse markets. This is a pattern among many collectors as they have more exposure and experience. Many collections do not have breadth using any measure, which results in a certain provincialism. We were very fortunate to discover art beyond Chicago.

In the early 1980s, Chicago had three or four galleries that primarily showcased local talent – faculty and recent graduates from the Art Institute of Chicago or University of Illinois at Chicago – and a handful of artists from both coasts. We went to local galleries routinely and we discussed art with artists, dealers, collectors, and curators. We regularly visited The Art Institute, the MCA, and the Renaissance Society. We saw everything Chicago had to offer: public and private, commercial and institutional.

By 1982, I had transitioned to a career in management consulting, which necessitated routine, often weekly, travel to New York. London and Los Angeles followed as frequent destinations. Whenever possible, Greg joined me on weekends in these cities. We immersed ourselves in galleries and museums. We were very fortunate to meet a group of artists and gallerists who would evolve and mature into the mainstays of the current international market. It was a time of exceptional potential.

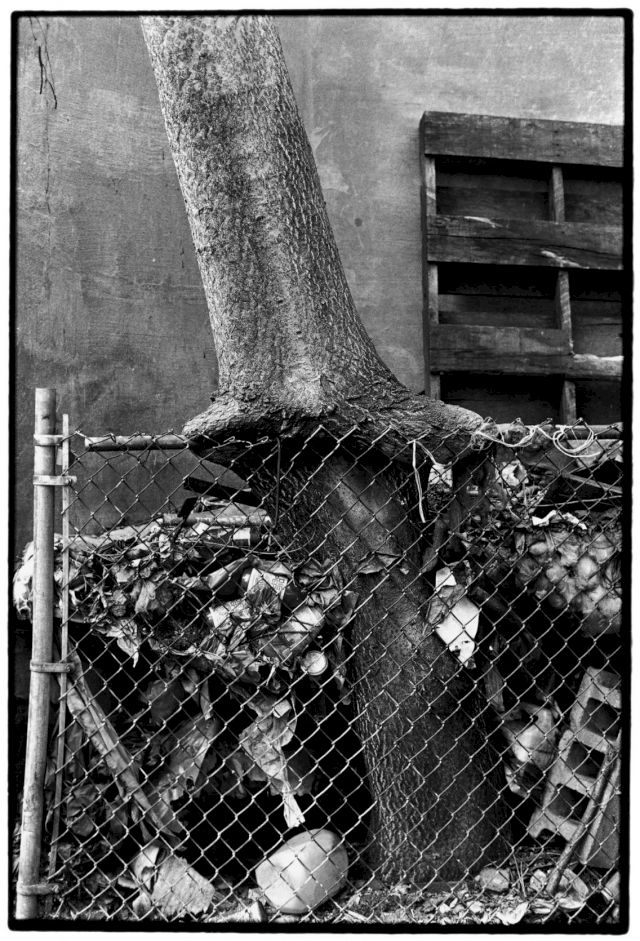

Galleries were not terribly protectionist then. Artists made their studios accessible. The social met the cultural in an easy mix. Music, performance, poetry, and art had few boundaries and fewer hierarchies. New York in particular was gritty and exciting. Collecting was not a competitive activity, nor was it conspicuously an investment strategy. There were a relatively small number of people – educated, but with middle class incomes – who supported the nascent East Village and SoHo art markets.

Theme and variation can be interesting, but we want to associate our collection with new ideas; ideas that make us think differently, ideas that challenge us.

CLAYTON PRESS & GREGORY LINN

IC

How do you buy art?

CLAYTON PRESS & GREGORY LINN

Direct experience are very important to us. We are gallery clients, first and foremost. But, we are also mindful that most of these relationships are transactional, retail relationships, which are very different than curatorial encounters. We visit galleries in person, via the Internet, and check in at art fairs, which we attend with less frequency. We write and speak frequently with galleries, dealers, and curators with whom we have developed professional relationships. We are directly engaged.

Yes, we look at online auction catalogs, but we are not typically auction clients. Why? We support the gallery system. We also feel that auction premiums and add-ons are nearly unrecoverable “taxes” on a hammer price. Auctions do not add to a work’s provenance, and sales results are generally false indicators of value, due to buyer’s premiums and the performative aspect of publicly buying from the auction house floor. But auctions do provide an element of theatre, even spectacle, to the art market, and keep a small number of journalists employed who obsess about personalities and prices. It is Kabuki.

The traditional auction house is now evolving into a hybrid of salesrooms, galleries, and advisory services. Now they often compete directly with galleries, mounting “celebrity” or “social register” curated group shows or even advocating their own artist discoveries. In our view, they – like the rest of the art market – are struggling to retain audiences and develop future clients. The recent shuffle of seasoned talent at the three major auction houses underscores uncertainty about that segment of the art market.

The smaller auction houses – Dorotheum (Vienna), Lempertz (Cologne), Van Ham (Cologne), and Rago (Lambertville, New Jersey) – often have some real gems. They also have interesting indigenous art, furniture, and design auctions. There are great values and interesting discoveries (or rediscoveries) at these auction houses. People over-concentrate on the big three auction houses and their night sales.

We are particularly wary about art – especially emerging art – that is marketed and sold via a website or social media apps. We are very open to new ideas and new ways of thinking, but we believe that art must be experienced first-hand and not by JPG alone. For example, we partnered in the first secondary market on-line retail site called The Spotlist/Collectors’ Spot. It was profitable but it was time consuming, and when the online space started to be cluttered with copycat retailers and auctions, we closed our web-based business. We were selling high-quality, secondary market work that had entered the canon, not emerging art that had accumulated a lot of Instagram “favs” and Facebook “likes.”

It is important to realize that the Internet art market is essentially about buying. It is all “pics” and buy-nows. The Internet is transactional activity. Buying art online is no different from buying anything else. Think about it. How many successful competitors do eBay and Amazon have? Amazon itself is barely profitable. Online sales offer product encounters, not art experiences. The Internet is for people who “think” they know what they want, and who want to get their purchases effortlessly. Genuine collecting is about an encounter.

The short lives of most online retailers and auctioneers are stories about ill-conceived business plans, unrealistic expectations of high volume, commoditized retail models, and – ultimately – vanity investments. Several entrepreneurs have tried to portray their businesses as disruptive innovations. Retail is retail. Real success in the art market requires perseverance and capital, which often comes through partnerships and collaboration. The Internet is a great place to learn – it is not a place to collect without assuming real risk, and not just financial risk. The Internet is an ocean awash with mediocrity.

IC

After many years of attending art fairs, you are very selective about where you go. One of them is Art Cologne. What encourages you to return to Art Cologne?

CLAYTON PRESS & GREGORY LINN

We have always been somewhat circumspect about fairs and their place in the art market. They are retail events, trade shows. We have seen dealers move inventory from Basel to Paris to Miami in a “ship-it-until-you-sell-it” strategy. We do not expect fairs to be “curatorial.” Talks, panels, and performances are rarely compelling, however to their credit, both Art Cologne and, more recently, Art Brussels have installed credible “inside the fair” exhibitions.

Peripheral events – talks, tours, and dinners – are often perfunctory rather than pleasurable or inspirational. There are exceptions, when you are fortunate to meet a gracious collector with impeccable taste and an alternate point of view. We are selective about which events we will attend.

Somewhat serendipitously, during Greg’s first visit to Europe, we happened on Art Cologne in 1982. There was a lot to see, given that we were new to collecting. But, from the beginning, most fairs felt and still feel like sensory bombardment. With 100 or 200 booths, plus an array of ancillary nonprofit and publisher booths, art fairs are exhausting both retinally and intellectually – it is impossible to absorb the range of content, let alone participate in meaningful dialogue. We feel fortunate when we can encounter work that engages us in concept and execution.

Art Cologne is one of the few fairs we have attended routinely, even more so than Art Basel. Art Cologne lets us meet dealers from Nord-Rhine Westphalia, as well as other German and European cities. We can renew personal relationships and conversations in Cologne. A week in NRW is invariably gratifying. In addition to the fair, Bonn, Cologne, and Düsseldorf have an excellent collection of first-rate academies, private collections, galleries and exhibition venues. Dortmund, Essen, and Frankfurt can be worthwhile side trips too.

We consider Germany the second most important art production center and art market after the United States. We are more inclined to participate in a market where work is made and sold, not just exhibited. Think about it, aside from a week in June, Basel is not a primary market. Ditto, Miami. Ditto, most art fair destinations.

We consider Germany the second most important art production center and art market after the United States. We are more inclined to participate in a market where work is made and sold, not just exhibited.

CLAYTON PRESS & GREGORY LINN

IC

How do fairs like Art Cologne influence your collection? Do you ever buy works at art fairs or is it mainly a social encounter?

CLAYTON PRESS & GREGORY LINN

Art Cologne is a “catalyst fair.” There is greater potential to see new talent, new art, and new ideas, but most importantly we can talk about art with local participants. We use fairs as additional channels for collecting, both for our clients and ourselves. Sometimes a purchase decision takes place at the fair. Sometimes it is a follow-up activity. But because of the scale and temperament of Art Cologne, we feel like we can really engage in discussion without feeling or succumbing to excessive pressure.

Also, we have usually received many preview documents in advance of a fair. These previews are potentially good sales tools for the galleries to educate and stimulate demand. Some galleries do an effective, sophisticated job at preparing these documents, but they can also be a turn off – they eliminate an important element of discovery and surprise. Likewise, over zealous marketing, via the Internet or social media – like Instagram – often undermines our motivation to even go into a gallery’s booth. That can be shortsighted.

IC

You have lived in some of the largest and – in terms of art – most important cities in the world. How has this influenced your collection? Is there a particular city where you primarily focus your attention?

CLAYTON PRESS & GREGORY LINN

New York is the epicenter of the global art market. This is not up for debate. The city and the region have the perfect convergence of colleges and universities, artists, intellects, collectors, dealers and galleries, auction houses, museums and Kunsthallen, media outlets, and economic muscle. No other city can challenge this rich complexity.

London has many, but not all, of the elements of a first-tier “artopolis.” For us, distance and costs are major impediments to doing business there. In reality, London is not a dynamic production center with a robust emerging artist scene. It truly is insular. If you look at London gallery programs, a disproportionate number of emerging and mid-career artists are Americans or Germans, not British.

Los Angeles and Berlin are highly respectable education, production, and exhibition centers, which is a side benefit of affordable, but increasingly expensive, real estate. But they are outposts. We have meaningful, productive, relationships with galleries in Brussels, Cologne/Düsseldorf, and Paris as well. We use both the telephone and email to maintain viable contacts as we thrive on personal interactions beyond text messages or any social media.

IC

Your collection includes a wide range of mediums, without preference for painting, like so many other collections. How do explain this diversity?

CLAYTON PRESS & GREGORY LINN

Our collection consists of ideas and media. We have never sought to limit ourselves to one thing or another based on media. We are adventuresome when it comes to ideas and fearless when it comes to media. Some collectors have developed really powerful statements in time-based media or painting; others have focused on specific artists or genre.

Painting is particularly problematic for us, even though it is considered by most to be the market king. We know collectors who suffer from media prejudice, excluding great works of art from their collections. It is a form of art blindness. That is, until one day they discover Christopher Williams or Zoe Leonard and have dye-transfer print epiphanies about conceptual photography.

A German collector friend once very accurately opined, “Almost anyone is capable of making one good painting.” This may be a truism worthy of Jenny Holzer or Barbara Kruger. Abstract painting is so pervasive it is difficult to differentiate it – it is totally manic. There is this onslaught of color and shape. Figurative painting is a different challenge. The narratives run the gamut from erotic fairytale to dystopian allegories. It is difficult to find genuine innovation in painting that is based on ideas and not gimmickry. What do you want on your wall? What will enter the canon? What will add to the dialogue? These are important questions that should challenge every collector’s decision-making.

There are similar problems with sculpture, installation, and photography. This is precisely why real education – even self-education – and dialogue is imperative. Follow @whos__who on Instagram – it underscores the enormous amount of monotony and recycling present in art making. The key is to be aware and informed. Consider this: no one has effectively redone or reinterpreted David Hammons, Robert Mangold, and Lawrence Weiner. Look how long and difficult it was for women to enter the canon: Louise Bourgeois, Isa Genzken, Louise Nevelson, and Rosemarie Trockel. These artists “own” their ideas and media. That is their genius, their contribution.

Being original, being an artist is an extraordinarily difficult occupation. It is hard work. There is a lot of room for failure.

IC

Within your collection you have numerous pieces by the same artist, creating an “overview” of an artist’s career, not just a “snapshot.” Why is this approach so integral to your collecting interests?

CLAYTON PRESS & GREGORY LINN

Let me answer with an example. One iconic Cindy Sherman black and white “Untitled Film Still” may capture the artist’s essence, but it is not an insight into how her career has evolved. Some of Sherman’s territory, like her dissembled mannequins and dolls, is a more difficult kind of genius. Many, if not most, collectors prefer iconic images that capture “the idea” and are more likely to retain (or grow in) pure economic terms. That is a safe and sensible way to collect.

We want to document an artist’s evolution as long as it is economically feasible for us to do so. We do not want one of this and two of that. We bought two modest paintings by Peter Doig, for example, at precisely the right moment in his career in the mid 1990s. We sold the work when we realized we would not be able to collect it in depth because of the sharp upsurge in his secondary market prices. About the same time, we began to collect work by Jason Rhoades. We were able to do so for several years. We have no regrets about our decisions related to the feasibility of long-term, in-depth support of an artist.

We were very fortunate to visit the Hallen für Neue Kunst (Schaffhausen, CH), very early in our collecting careers. There you could see dozens of Andre’s, Nauman’s, and Ryman’s. You can see a similar approach at Dia:Beacon, where there are expansive collections of Chamberlain, Flavin, Judd, Martin, and Sandback. You get it. When we look at museum collections, we have been struck by collector commitments to genre and artists. Leonard Lauder’s Cubism bequest to The Met in 2013 was and is jaw-dropping, inspiring.

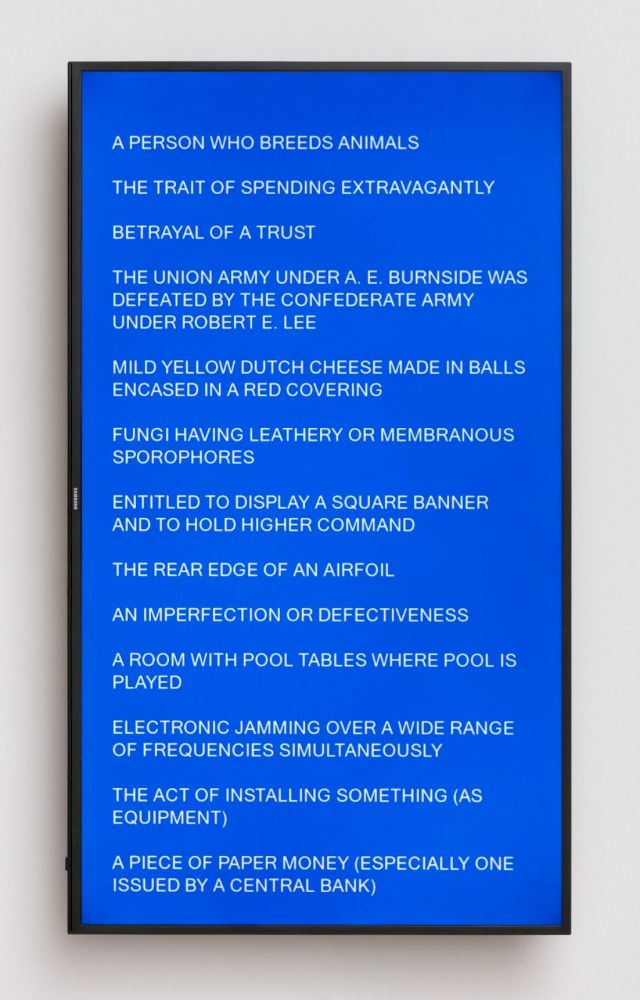

Our approach is to develop portraits of artists’ careers, collecting several works – 5, 10, 15 – over time. For us, we are most interested in making a commitment to artists who are doing something fresh and evolutionary. We own paintings, time-based media, photography, sculpture, installation, and even several URLs (domain name and web application). Here is an example by Damon Zucconi, www.dictionary.blue.. By supporting these artists longer term, we feel – rightly or not – that we are encouraging them to push forward and through.

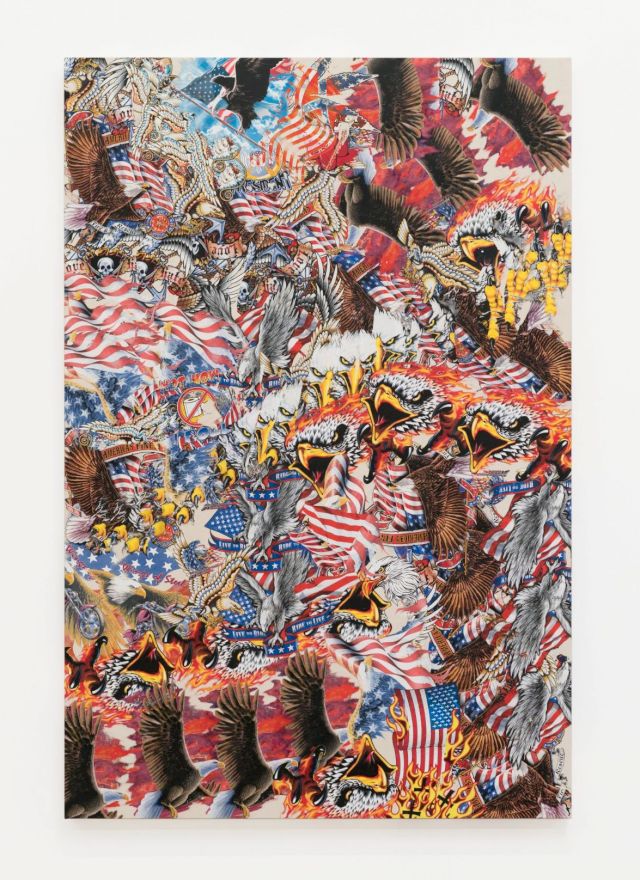

We took this approach first with the Pictures Generation, and then we did this with artists like Angela Bulloch, Stan Douglas, Zoe Leonard, Jason Rhoades, Kay Rosen, Diana Thater, Franz West, TJ Wilcox, and Christopher Williams in the 1990s. Next came, Matthew Brannon, Wade Guyton, Jutta Koether, Seth Price, and Kelley Walker in the 2000s. Now we are making similar, deep commitments to artists like Adam Henry, Jacob Kassay, Win McCarthy (whose work we first saw at Art Cologne in 2014), Borna Sammak, Kyle Thurman, and Damon Zucconi.

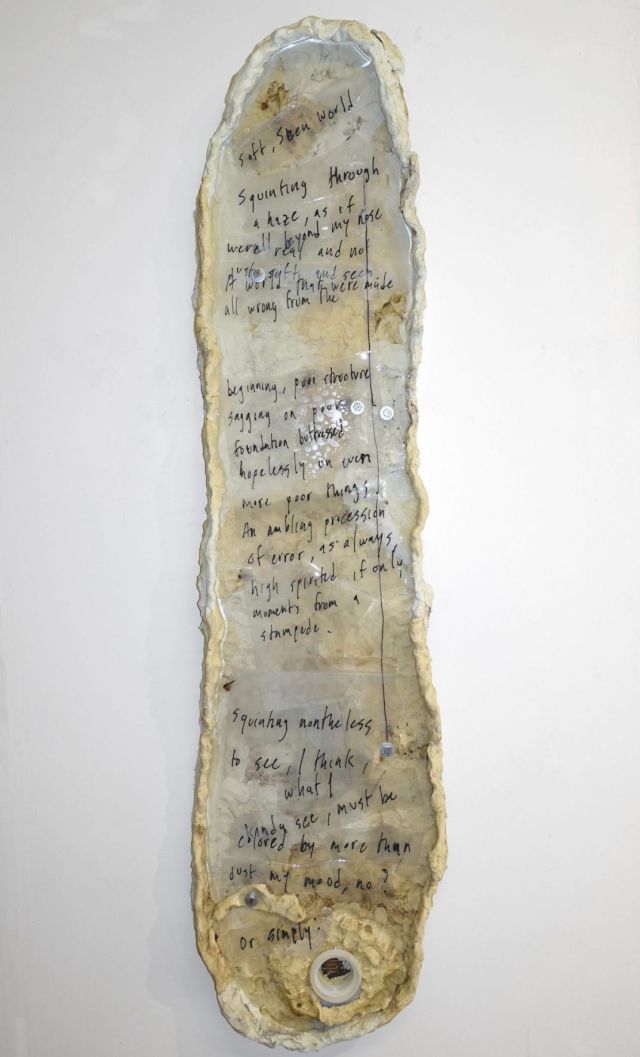

Kassay epitomizes the type of artist who engages us. We own several works by him, but ironically not an electroplated silver canvas (although we have placed them in several private collections). The works we own are diverse and conceptual, and they demonstrate a complex intellect. Likewise, the work we own by Thurman shows his intellectual consistency alongside his natural fluidity as an artist. His drawings are staggeringly beautiful, lyrical in stark contrast to a highly minimalist sculpture we own.

Many, if not most, collectors prefer iconic images that capture 'the idea' and are more likely to retain (or grow in) pure economic terms. That is a safe and sensible way to collect.

CLAYTON PRESS & GREGORY LINN

IC

How do you live with art? Do you sometimes fall out of love with a work, but then find yourself appreciating it again at another time?

CLAYTON PRESS & GREGORY LINN

We live in an average American house that doubles as our offices. There is art in every room, but the art has room to breathe. There is better-than-average storage, and we are very self-contained and organized.

Depending on the size or circumstances, when a new work enters the collection, we invariably find a place for it (URLs residing on the Internet are especially easy to store and display). Much of the work is a domestic size, so in one hallway, for example, we have twelve Zoe Leonard photographs hung salon style. It works. But we also have flat files and storage racks for works that we either rotate through the house or we loan when the occasion arises. Then, there is the basement full of video monitors, DVD players, and crates.

We are quite happy with the work we have. We never really fall out of love with a work or an artist, but we are always open to rethinking how we might be looking at a work, its context, and relationships to other art. We recently opened a box and discovered a 40-piece collection of 1970s era Scandinavian cased glass that we put together when we lived in London. That was a delight, but we immediately re-retired it. On the other hand, we opened another box filled with ethnological material we had bought in Java and Bali. These works have recently emerged from storage.

Many collectors do not have inventories or data management systems. We consider this naïve, even dangerous. We have maintained a detailed electronic database for almost 20 years, first on a spreadsheet, now on a cloud-based system. It took effort and dedication to build the database, but the details of almost every art object we own are at our fingertips. In addition, we have paper-based archival files on every artist where we own three or more pieces. This is somewhat redundant, but it makes the concept of collecting more cohesive. Likewise our art library – some 1 000 plus volumes – expands the depth and breadth of documentation. The fact that we had accumulated and maintained artist-related documentation and ephemera made our collection more attractive to The Met.

IC

You recently negotiated the bequest of your estate with The Metropolitan Museum of Art. What precipitated this relationship as opposed to other museums?

CLAYTON PRESS & GREGORY LINN

We have gifted works to museums in Canberra, Chicago, Los Angeles, New York, Philadelphia, and Princeton. Our philanthropic strategy has always been to share our collection where we are fulfilling an interest or need. There has to be alignment.

As for our estate, we chose The Met for several reasons. Foremost, the museum has made a strategic commitment – or perhaps recommitment in the post-de Montebello era – to advance its contemporary collections, and its approach is truly international. The Met just announced a partnership with Saudi-based Art Jameel to add more modern and contemporary work by Middle Eastern artists to the museum’s holdings. This is very forward thinking.

The Met has seventeen curatorial departments. Its holdings interact with one another, and it is not a just a modern and contemporary art museum. The art historian Hal Foster, who teaches at Princeton, has said that this dynamic exchange at The Met is “exactly what New York needs at this moment, when there’s such a stress on presentness and the fascination with ‘now.’ ” The Met is one of the most important encyclopedic museums in the world that values dialogue and scholarship – intellectual acumen. We have invested a fair amount of “gray matter” in collecting. The Met will continue this commitment, finding linkages we never made. This is very exciting. Imagine a Mark Leckey video being shown under the same roof as the Temple of Dendur. It boggles the mind.

The Met also represented an opportunity for us to make a transformative bequest. They are building their contemporary art holdings, looking to the long term. There is very little overlap between the museum’s current collection and ours. So in one fell swoop, the museum will have nine Diana Thater video installations along with several of her works on paper, where previously it had none. This will also be the case with several other artists: career histories.

Perhaps most consequentially, we realized that it is more important to have a relationship with an institution and its future plans and not just with its curators. This may sound odd. We respect every curator we have met on The Met’s team. The graciousness and professionalism we have encountered is exceptional but ultimately our relationship is with the museum. That is most important to us. Curators and directors come and go, but the institution remains. We keep the museum informed of what we are doing, but any decisions about the collection are ours.

IC

How do you feel your collection will play a role for visitors to The Met in the future? Does the notion of having an “educational” collection factor in when you make a purchase decision?

CLAYTON PRESS & GREGORY LINN

We hope we are not only enriching The Met’s collections, but also expanding on the ways in which art can interact and inspire. The Kolumba Museum (Cologne) and Museo Internacional del Barroco (Puebla) are two newer, specialized museums that demonstrate how contrasting genre art can co-exist and inform contemporary projects. This is exhilarating.

Our “transcendent” moment with The Met was its first exhibition at The Met Breuer. Entitled “Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible,” this exhibition questioned the very notion of completion, asking “When is a work of art is finished?” The exhibition had about 200 works dating from the Renaissance to the present, demonstrating the museum’s ability to dig deep into its own collection and work with other lenders to present modern and contemporary art in strikingly different ways. To us, this was an exceptional educational service, and a lesson in connoisseurship.

Coincidentally, when The Met Breuer presented Kerry James Marshall’s recent solo show, Marshall selected a few dozen works from The Met’s collection to underscore the range of art historical influences on his own work. Marshall’s inclusion of other artists’ works within his retrospective was revelatory, brilliant even.

The ability to learn about, understand, and collect art is a gift. This is lost on many people, who engage in the art business as a speculative transaction or a mechanism to climb some imaginary, but rather rickety, social ladder. We have always distinguished the art market from the art world.

We are unusual in that we are both in our 60’s and are still actively collecting. Many collectors have arcs or cycles and many more just stop. We consider ourselves extraordinarily fortunate to collect some artists who we believe will contribute to art history. We follow our own path.

Many collectors do not have inventories or data management systems. We consider this naïve, even dangerous.

CLAYTON PRESS & GREGORY LINN

Clayton teaches art history and art market economics at New York University and has research privileges at Princeton University. He recently wrote the catalog essay for “Robert Mangold, A Survey 1965-2003” (Mnuchin Gallery, 2017) and “Next to Nothing, Close to Nowhere”, a monograph about the work of Kathleen Jacobs (Burckhardt Boles, 2016). Clayton is also a regular contributor to Arteviste.com. Gregory manages both qualitative research and quantitative analytics for consulting engagements.