Independent Collectors

Ovidiu Șandor

Confident elaborate uncertainty

«Art is a great helper in keeping this critical thinking about our own assumptions, about our own understandings.»

A conversation with Romanian collector Ovidiu Șandor in Prague.

Sometimes spaces arise out of love and someone's strong belief that such a space is necessary. Thus, Kunsthalle Praha was born in Prague, a vast and well-equipped art space consisting of three galleries in the former transformer station building that used to power Prague trams before they climbed the high hill of Petrin, one of the city's attractions. Electrical equipment is still kept in one of the rooms, and while transformers used to occupy the whole building of several floors, now one room is enough for them – such is the spatial dimension of progress. The building devoid from its original function was acquired, reconstructed and equipped with a new mission by The Pudil Family Foundation – private initiative of Pavlína and Petr Pudil, a family of collectors and contemporary art lovers. “Our name, Kunsthalle Praha, alludes to Prague’s multicultural past as a city of three nations, two languages, and one unique charm,” reads the text on the KP website. “Our mission is to contribute to a deeper understanding of Czech and international art from the 20th and 21st centuries”. This allows the institution both to focus on the history and trends of global contemporary art and to present a more diverse picture of the art scene in Eastern and Central Europe.

And this is what the exhibition Lost in the Moment That Follows, opened here in mid-June, is about. The title of the exhibition is a quote from Andre Breton, the founder of surrealism, which emphasizes one of the focuses of the exposition – the relationship between past, present and future. The show is dedicated to Romanian art from modernism to present day contemporary and is a selection of works from the collection of the famous Romanian art philanthropist Ovidiu Șandor, the founder of the Art Encounters biennale in Timișiaru, the city where Ovidiu lives. The exhibition of 139 works by 79 artists was conceptualized and shaped by curator Tevž Logar and is on display until September 11. It is a continuation of the Ways of Collecting exhibition series conceived by Kunsthalle Praha, which was launched last summer with the Midnight of Art: Karel Babíček’s Collection show. Christelle Havranek, Chief Curator of Kunsthalle Praha, explains the Ways of Collecting concept: “With this exhibition series, we are highlighting the activity of collecting, which – although often ignored – is an integral part of the artistic ecosystem. In the Czech Republic especially, where for many years art collections were accessible to the public only through state institutions, the role of private collectors remains somewhat of a mystery. Who collects what, and why? What is the relationship between art and collecting? And are artists themselves collectors? Our series aims to offer answers to all these questions and many others.”

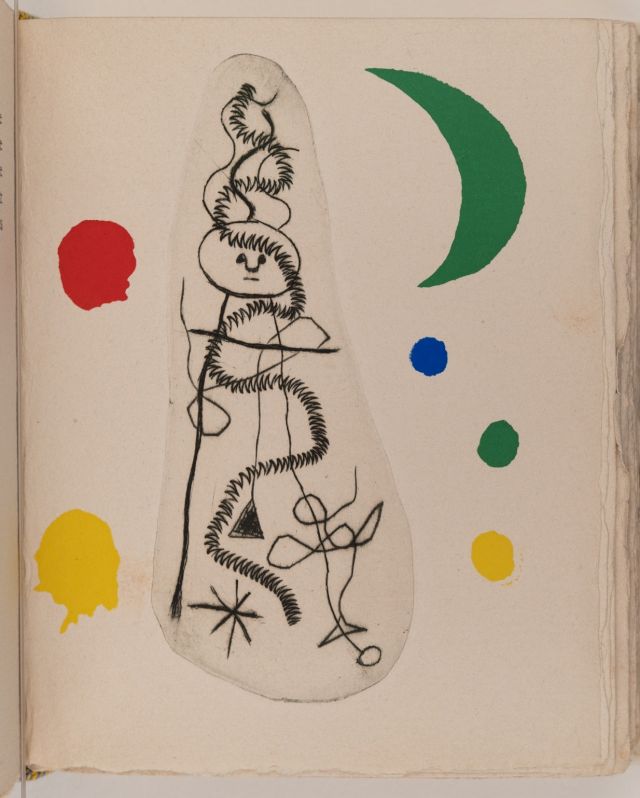

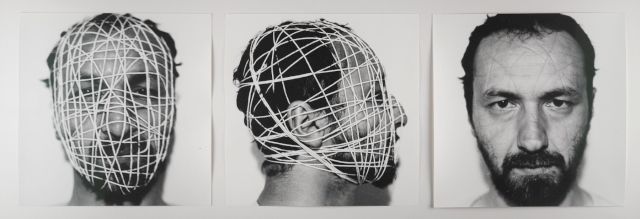

In this sense, the collection of Ovidiu Șandor can serve as an excellent example of an approach to collecting both as a pleasure and expansion of one's own horizons, and as a kind of mission with a wide cultural impact. Having found a special interest in the art of his country, Șandor did a great job of making it more visible in the international context, of showing its relationship to the global art scene, of structuring the concept of its development over time. This is exactly what his Art Encounters Foundation and the Art Encounters Biennial organized by the foundation do. The collection does not have its own publicly accessible space yet, but its works constantly appear at various exhibitions both in Romania and abroad. It features Constantin Brâncuși, Victor Brauner, Brassaï, André Cadere, Ciprian Mureșan, Ioana Nemeș and many other artists who, each in their own way and media, have expanded the possibilities of art. Therefore Lost in the Moment That Follows masterfully conceptualized by curator Tevž Logar is structured not chronologically, but according to the four themes: identity, nature, space, body and memory, representing interconnection between the works from different eras and different media: from paintings and sculptures to installations and videos. Moreover, books, publications of the 1920s surrealists also play an interesting role in the show, being a very peculiar and important artistic media, whose potential was then acknowledged by the artists once again and used by them in an extremely effective manner.

We arranged a conversation with Ovidiu Șandor right after the press tour of the exhibition, sitting at a table in the Kunsthalle Praha cafe. He spoke confidently, thoughtfully, and never seemed to hesitate with an answer, probably because he was talking about things that he had thoroughly thought through already. After all, his collection and his approach to the very process of collecting is, of course, a constant process of awareness: the multiple viewpoints, the interesting complexity of the world and its structure – both historical and contemporary. Having been asked during the press tour what he learned from collecting, Ovidiu replied:

“History is very nuanced, it’s never black and white and especially in complicated times… For different people the perception is very different and you see it in the works of the artists reflecting on it. I guess, it’s not so much that I’ve learned from art, I rather understand that I don’t know enough. I have a friend, he is an architect and he has this saying: “I’m only afraid of people who do not have uncertainties”. What I learned from the artists and from collecting – I gathered more uncertainty, and I found it very helpful, at least for myself.”

According to Ovidiu Șandor the world map features a vast variety of shades and tones, everything except for white and black. And the awareness of such things makes even our doubts more confident and thoughtful, and our worldview – fuller and richer.

Sergej Timofejev

As an entrepreneur you operatе with real estate, with buildings and spaces, which are like huge pieces of our reality constituting our world. And as a collector you started with antique maps. Maps represent the reality of the world, but in a more abstract way, on a scale of reality indistinguishable for a naked eye. And then you moved to collecting works of modern and contemporary art, which are also ”maps of our world” but at an even more abstract or virtual level. Even if they are physical objects themselves at the same time. How did you make this step from maps to art in your life?

Ovidiu Șandor

I think it was a bit of a thing that just happened. Most of the old maps are engravings. And antique maps were not so instrumental as they are nowadays, it was a much more artistic type of an object. Old maps have this artistic quality. Ehen I was arranging a new office, I happened to visit a hotel where they had an auction called “Black and white”. And they were auctioning engravings and by the classical, modernist painters of Romania that all the kids learned in school about. Because they were engravings, they seemed very familiar in a sense – like the maps. And I thought that it might be a good idea to buy some engravings and some drawings by these quite known Romanian artists from the 1920s and 1930s, and put them in the conference room in the office. It was all almost by chance.

And then quite soon after I met a couple of young contemporary art gallerists. And quite fast I moved from engraving to a wide range of media – from painting to installation and so forth. And these gallerists I met started explaining to me, what contemporary art was and how to look at it and all that. I realised I was less interested in classical modernist art, but felt a real connection to contemporary art. And then I discovered the avant garde of the 1920s and 1930s. So I focused on these two components: the historical avant garde and all the post WWII contemporary art. And then it's sort of one thing leading to the other… You go to an exhibition, you discover a new artist, by discovering that artist you talk to somebody else, and you find out about other things that you should read about. Then when you start reading about an artist, you start understanding that there’s, maybe, a whole artistic context in which that artist was active. And then you start your own exploration in various directions, obviously, in a very personal manner – it's not like going to the school of art history where you have to read about certain things. When you collect you can be interested in what you want to be interested in. With all the advantages and disadvantages that might come from that. But yes, that's how I moved from collecting maps to collecting art.

Sergej Timofejev

What part of your personality, what part of your identity is connected to this process of collecting?

Ovidiu Șandor

I don't know. I guess collecting in itself, especially when you do it intensively as collectors normally do… This compulsion of not only appreciating art, but having it, probably has some sort of scientific explanation. I always say that psychologists and psychoanalysts might have a Latin name for it. I guess it's also a sort of condition. I think the urge in my case is to explore who we are, who I am. And to understand that, of course, we need to look at where we come from. And that's probably why in the collection you see quite a lot of works that refer to recent history, the history of Romania, the history of Europe of the 20th century; as well as nowadays issues. In a sense I try to understand what direction we go – as individuals, as a city, as a country, as Europe. For me it's very interesting to see how the artists perceive the world and the issues that surround us – political issues, sustainability issues, social issues, economic issues, aesthetical issues, cultural issues and so forth.

Like many collectors, I'm rather an analytical type of person coming from the business world that at least from the outside seems very dry and figure based, goal driven and deadline oriented. And of course, that comes with looking at the world in a certain way. For me artists are unveiling a totally different way of looking at the world; the way that is much more sensitive, much more personal, much more human. They look at different issues or look at the same issues in a different way. And that's probably what exploration of art gives to people like me. You understand that your opinions about the world aren't the only way to perceive the world. But it's just one of the ways to understand it. It's like adding doubt to what I know about the world. And I think that's an important part of critical thinking – to question your own beliefs about the world. That in a way explains why I do this.

Sergej Timofejev

When a collection comes to a certain level, when it’s not just your favourite art pieces on the walls, I think, sooner or later the urge to have the art you really like gives way to the need of building your own model of the universe around you, your own mega-map with this collection.

Ovidiu Șandor

Yes, in a way. It happens when a collection starts being more than the sum of individual works. And of course, now, when I purchase a new work, I always think not only about “is this a good piece of art, what does it say, what does it mean”. But I also think about how it relates to the rest of my collection, how it contributes to this collective of art pieces, how it connects dots with other pieces in the collection or with other artists in the collection. It is much more than just a number of artworks that are being purchased. And after a while you start thinking a bit more structured, in what direction you want to take your collection. Of course, there're always artworks that you will never be able to possess – for various reasons. And you always think – with the limited resources that you have (time, money and space) – how can you make something that is as articulated as possible, as relevant as possible? Indeed, at some point you start thinking about this meta level of what the collection is.

In Eastern Europe especially, we, collectors, have certain responsibilities that are in a way bigger than the Western European collectors’. Because in some Central and Eastern European countries public institutions are still not always very active, they still don’t have enough resources for it. And we have this role of helping to keep a number of relevant artworks from this region in this region, rather than be sold to museums or private collections in other parts of the world. I don't have anything against that. But I think it is important that a relevant corpus of relevant art stays in the region. And I do think that this generation of Central and Eastern European collectors will get this role. I also think that a number of what are now private collections will, with time, become publicly accessible collections, either in public institutions or in private museums or elsewhere. I think there is this responsibility that, for example, a West European or North American collector doesn't necessarily have – because there you already have many public institutions or long standing museums that are actively collecting and actively displaying art.

And then the other function I find important for my collection… I see it as a responsibility to make the collection or the artworks and the artists of the collection visible. And that's why I'm very open to lending works from my collection to various exhibitions in the country and abroad. Because, again, that offers additional visibility, especially for the young artists. To all those I think important in the art scene of Central and Eastern Europe. That is still, of course, an art scene that is not yet mature, it has progressed a lot in the last 10-15 years, from almost nothing to a scene that now has a vibe, and you have new institutions popping up like Kunsthalle Praha, you have new events, you have exhibitions, you have artists running spaces, showing up in all corners of the region. But we're still far away from a mature art scene. And in this context I think it is important that the private collections circulate and are visible publicly in various types of exhibitions, not necessarily exhibitions dedicated to a certain collection, but allowing these collections to be resources for curators and institutions doing various types of exhibitions.

Sergej Timofejev

If we take this metaphor of a collection as a private model of the universe further, Romania and Romanian art must be in the centre of your universe. Is it possible to describe in a few sentences your feelings about your local art scene?

Ovidiu Șandor

I think obviously Romania and a number of countries in the region share a common history. And at the same time, each country and its art scene is unique. It is very interesting to look at these similarities and differences in the region. The art scene in Romania, as in any other place, has been very much influenced by its history. We had a very strong generation of avant garde artists between the two World Wars, who were extremely well connected internationally for that time. They didn't have the internet, they didn't have cheap flights from Bucharest to Paris. Instead, they mailed letters, they published magazines and books that they would circulate. And I think, for example, Tristan Tzara (who is also presented here in the exhibition) was one of the first influencers in art. He wrote to artists all around Europe, frenetically spreading the ideas of Dada in the way that today somebody would do using Instagram or a blog or something like that.

So I think that's a fascinating part of the Romanian contribution to the international art scene. It was a period when Romania was also having an interesting social and economic development with its advantages and disadvantages like in any other part of Europe. Then, of course, Romanian art was very influenced by the communist period, where artists would either enrol within certain ideological lines and have quite comfortable and easy life or they would do art that was not necessarily illegal but was outside the official guidelines. And that very often meant that those artists could not show their art, could not sell their art and thus had to live in more difficult situations. But there were artists that combined these two attitudes, on one hand, doing what was needed to survive, and at the same time, in their own studio exploring very freely, what they felt for. Of course, that is reflected in Romanian art and you see the similarities with a number of artists in other places in Europe – from Poland to Slovakia or ex-Yugoslavia.

After 1971 Romania closed itself culturally from the West. So, unfortunately, it was a very tricky time. And I think it’s reflected in the art of that time. And then, of course, after 1989, we had a very complicated period, especially in the 90s. With this sudden transformation from communism to democracy and capitalism, which was obviously a very painful transition, also for the artists. And that again is obviously reflected in their art.

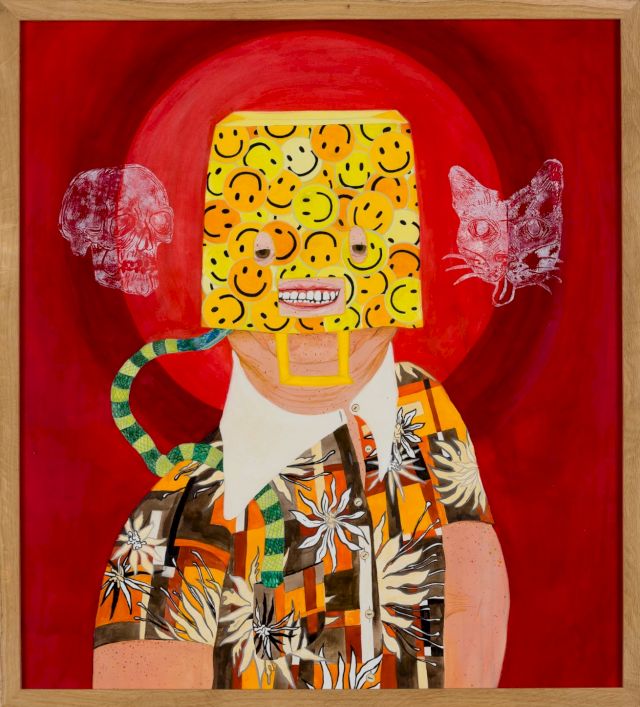

In the last 10-15 years the art scene evolved and developed, and various initiatives and institutions appeared. We see now that younger artists do not refer that much to recent history, especially the young artists that were born after 1989 and never experienced Communism. They become a more universal type of artists, much more interested in the universal themes of art – from the social issues to the ecological issues and other subjects that are relevant for the international art scene. Of course, they look at it from the perspective of a young artist living in a country like Romania. But I think they are much more in sync with the present-day society, and maybe less concerned about the past.

I think there are certain points in Romanian culture that are similar to other Eastern European cultures. And you can see that in the works of art as well. I think there's a certain component of absurdity and willingness to laugh even in tragic situations. Or this Dada approach of turning all the serious things into a kind of unserious play, which at the same time is serious indeed.

Sergej Timofejev

Another level of seriousness.

Ovidiu Șandor

Yes, you first laugh, but then you understand how deep it is. I think that's something that Eastern Europe and even Russian culture have in common – in literature, in philosophy and in art, and in theatre. Then, I think, Eastern Europe has something that has to do with a form of spirituality. Because we come from societies that traditionally were much more spiritual, I don't want to use the term religious, because we're also talking about traditions that predate Christianity. But all these stories that are being narrated for generations about mystical creatures in the forests of whatever country in Eastern Europe, the religious spirituality, which of course for Western Europe is not so present, because it’s been a more pragmatic society for quite a long period of time. I think spirituality is something that might not be explicit in the works, but you still feel it – the references to the cosmos, to the universe, to things that are unseen or outside of our world. I think it's something that is present in East European art.

These are some fundamental points that I see here. But of course, at the same time, each country has a very different path. A country like Poland was way more open in the 80s, when Romania was totally closed and in a very degraded state of society. Which is also reflected in Romanian art.

Sergej Timofejev

When we're speaking about artists from the Eastern European region or Central European region… Do they still need some kind of recognition from the Western countries, from curators, critics and collectors “from the West”? Do they need it first to become successful in their region?

Ovidiu Șandor

It’s a very good question. Yes, I think this recognition is something that is useful. And of course, this comes with its advantages and disadvantages. Obviously, there is a critique of the fact that our East European societies have this reflex of always trying to see what the West thinks about us. Even if I can't really frame it in colonial terms, as some people may frame it, one might see it as a reaction of the periphery towards the centre. It is the reflex a smaller brother has towards an older one, even in a family. So in a sense, I think it's natural, but indeed, I think we should trust ourselves more. It is important that we as a region and us as countries and individual artists, that we create identifiable voices, that don't necessarily wait for this approval. I also think that we need to look more at ourselves. Institutions in Eastern Europe should look more at artists in Eastern Europe, gallerists in Eastern Europe should look more to refine collectors from Eastern Europe, Eastern Europe collectors should look more at creating structures or events in Eastern Europe, and not only supporting West European institutions in acquiring East European art. And by looking at each other more, and maybe talking more about it, working closely together, we can make our region’s art more visible and more relevant in the international art scene.

Several weeks ago in Bucharest we had the first really relevant contemporary art fair, called RAD, very small – about 20 galleries, but all the right galleries. And they were surprised to discover how many people in the country were collecting. Because some of these galleries are more familiar with international collectors and don’t even know all the collectors in their own country. And I think that happens all over Eastern Europe, that we have this reflex of connecting and mirroring ourselves in the international art scene. We start to be interested in each other when someone becomes visible in the international setup, instead of maybe spending a bit more time and effort on getting to know each other. And I think that's where, for example, Kunsthalle Praha begins to really contribute. We also hope to contribute with the Art Encounters Biennial, where we try to bring together Romanian artists, East European artists, and then place them in an international context. And there are other initiatives. So we don't always have this reflex of looking in the western mirror, and start appreciating ourselves directly without this intermediate. On the other hand, I do strongly believe that the only relevant art scene is the international art scene. I don't believe that we can have art scenes in our own countries or in our region that are disconnected from the international dialogue. I don't think that's possible any longer. But indeed, we shouldn't always look for this sort of confirmation.

Sergej Timofejev

You said art gives you this feeling or understanding of uncertainty. It’s been four years now that we live in uncertainty – first the pandemic, and now – the Russian war against Ukraine that’s been on for a year and a half now. It seems like your focus on avant garde art is somehow connected to this situation of uncertainty as this art was created by people who had experienced the First World War and it was kind of a reaction to it. And now we look closer into this field of art to find the answers to the issues of today.

Ovidiu Șandor

Obviously, the avant garde and all its versions, from Dada to Surrealism, were very much reactions to the First World War, when the world order was turned upside down, politically, socially, economically and humanly. And I guess it was their way to try and cope with that sudden change. I don't know if the war in Ukraine will necessarily have the same level of impact, but obviously it does question certain priorities even in the art world. I think it does question if the subjects that the art world was concerned with before the war in Ukraine, were really the most important subjects. The priority of the topics have changed, I think. And of course, this will create a context that I believe will lead to surprising new art and new approaches, because it is something that is shaking the system, even the art system. It makes us question what is important for us as individuals, and what is important for our societies? What is important for our future? I do think this will transform the art world, probably in very relevant ways. Who will be the key artists in this transformation – is probably impossible to predict. But it's a context with a lot of ferment in it, it will generate a lot of chemical reactions and will lead to things that may be very important for the future. Our generation has been very spoiled because we lived for such a long time in Europe without wars. And we took a lot of things for granted. Now we took peace for granted. After 1989 we took liberty for granted. Of course, the young people born after 89, they took it for granted from Day One. We took freedom of speech for granted. And now suddenly we realise – they're not really as granted as we thought they were. I'm really looking forward to seeing how that will reflect in the art of the coming years.

Sergej Timofejev

But how do these avant garde artworks from the 1920s and 30s are functioning in the contemporary world?

Ovidiu Șandor

I think art is what happens between the artwork and the viewer. And obviously, we differ from the viewers of the 1930s. The same artefacts will have a different meaning for us today. I find it very interesting that in the last few years there were a series of surrealist exhibitions. But it’s not that strange if we take into consideration the context of the Ukrainian war or the situation of a society that doesn't really know what direction to take. It shows that the surrealist way of looking at the world, at all the things we don't physically see in the world, is something that people are still concerned with.

In Timișoara we just had a Victor Brauner exhibition which had a huge public success. So that only means that this art still evokes emotions and thoughts and questions in the minds of present-day people. I think that's clear proof that it continues to be very relevant. It’s clear that, as a society, we have not solved the issues that existed at the time when these works were created, we might have tried to solve some and maybe even succeeded in some ways, but other issues remain to be addressed. Everything from identity to society or national issues: what is more important that you are Romanian or Polish artists? Or that you're a European Union citizen? I think those sorts of issues existed then, exist today and probably will exist in the future.

So yes, I think it is relevant through our own perception. And, indeed, I think it's quite nice what Tevž Logar, as curator, did in the “Lost in the Moment That Follows” exhibition – he juxtaposed works from very different times, but they somehow address the same questions, the same issues, or suggest the same explorations. I also think that non contemporary art is important today because it reminds us that many of the issues are not that new. And questions we need to deal with are not entirely new, and the solutions we find are not necessarily new either. I think this gives us a bit of perspective. We always think of ourselves as the smartest generation, as the ones who brought the solutions or at least attempted to find them. And I think this is a very kind reminder that other generations before us went through the same turmoil. Through the same issues they probably found similar answers for, or maybe different answers. But our struggles are nothing new.

Sergej Timofejev

Does this influence your view of the future in some way?

Ovidiu Șandor

I think, obviously, it does. I don't know how but you know, art always changes people, those who begin having an interest in it and following it and understanding the various layers of various artworks. I'm sure we, as humans, are changed by that, and this will change our future. On the other hand, I don't necessarily think that, for example, a certain type of militant art that fights for or against certain things, is directly changing society. But I think in a broader sense art transforms people and then people transform society. I see it as a more indirect tool for changing society and not necessarily a direct tool for certain militant positions. I'm a bit more sceptical of art’s ability to change society directly.

Sergej Timofejev

I loved your remark that the experience of communication with art let you appreciate the uncertainty. Where uncertainty is understood as something rather positive.

Ovidiu Șandor

I do think that when people have too much certainty, that leads to problems. You know, that's the case of dictators: they think that they know exactly what needs to be done and how it needs to be done. And it always turns out bad, especially for the people. While having a dose of uncertainty about ourselves keeps us sane, I think. Art is a great helper in keeping this critical thinking about our own assumptions, about our own understandings. That helps us to be hopefully better people going forward.

Sergej Timofejev

What are your future plans for your collection?

Ovidiu Șandor

Until recently I focused on Romanian art only. But in the last couple of years I started exploring, and if we use your metaphor of cosmography, I'm now exploring two circles around the Romanian art scene. The first circle is kind of obvious, it is the broader Central and East European art scene. And I've started slowly acquiring works of artists from this region. And the second circle is the broader international art scene, where again I started collecting certain artists or artworks, but that all somehow relates to the core of Romanian art. I'm looking for those artists and artworks in Eastern Europe and in a broader international context that somehow relate to the practices or maybe historical moments or somehow are engaged in a dialogue with this core of the collection, which will remain Romanian. That's the new direction that I try to give to my collecting. It's in very early stages now. That's why this exhibition, for example, continues to focus exclusively on Romanian art. It will take time to build up this East European and international set of artworks within the collection before it can be displayed together and make sense somehow. But that's the plan with the collection at the moment.

This interview was originally published on Arterritory.